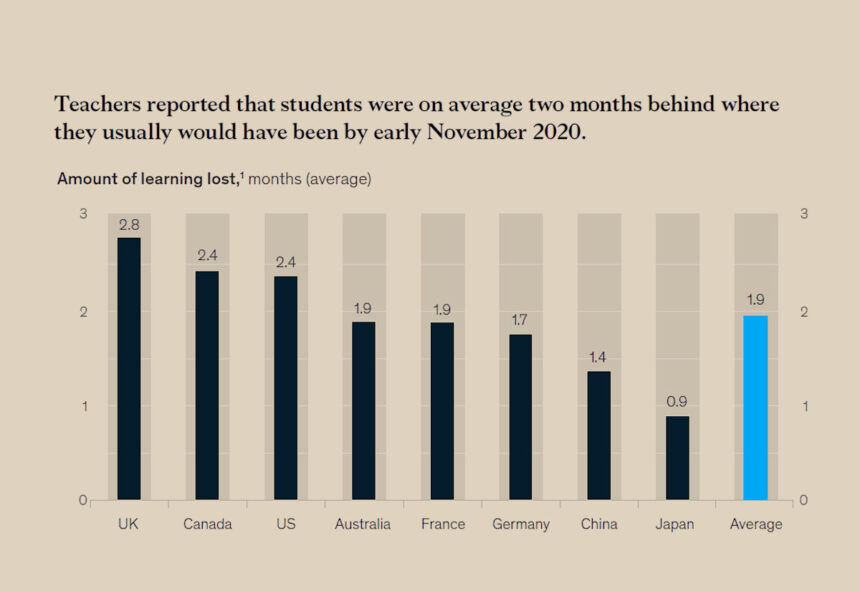

School shutdowns at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic may have put students on average two months behind the learning they would have usually achieved by early November 20211, in spite of widespread resort to distance learning as an alternative.

Teachers had consistently pointed to missed assignments and falling test scores as clear indications of disengagement and learning underperformance. This anecdotal evidence has been confirmed by research conducted in several countries.

That delay seems to have been greater in math than in reading, and also slightly greater for younger students (2.2 months for kindergarten through 3rd grade versus 1.7 months for 9th through 12th grade).

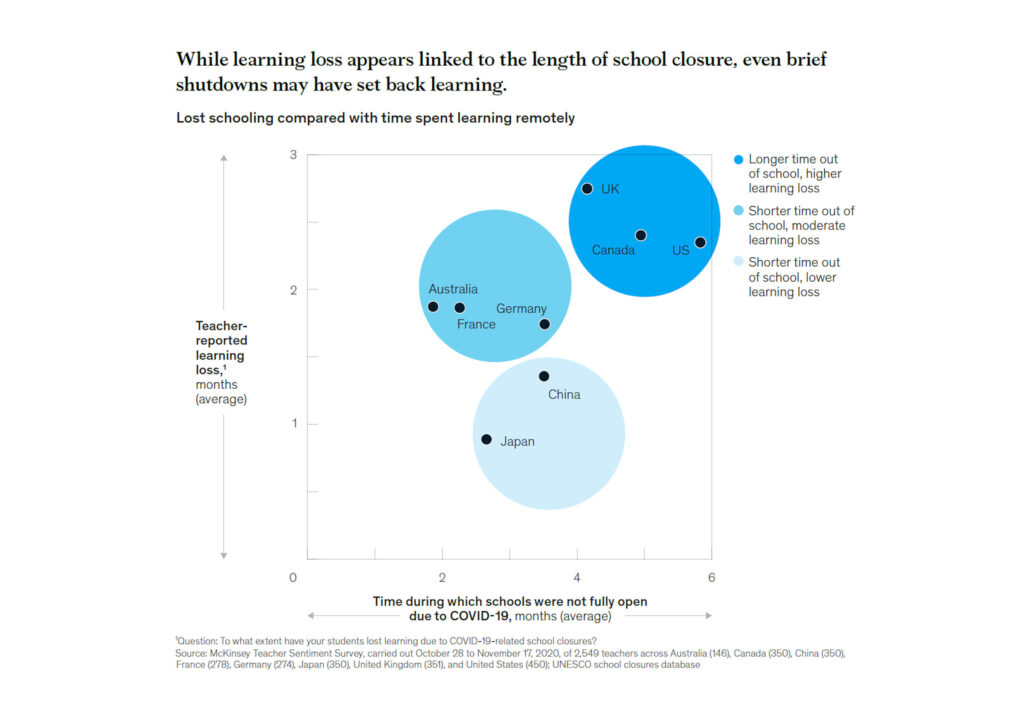

Research by McKinsey shows that learning losses diverge significantly between countries, with the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States more severely hit, and Japan, at the opposite end of the spectrum, reporting just a 0.9 month delay (see cover chart). These differences suggest that the duration of the shutdown is a good predictor of learning losses (see Exhibit 1).

Considering that many countries subsequently faced repeated shutdowns and intermediate periods of blended, in-person cum distance learning solutions, it’s too early to fully assess the cumulative impact of the pandemic on academic outcomes, but there are reasons to fear that students will pay a heavy toll.

This is compounded by emerging evidence that the stress and isolation of online learning is contributing to mental health issues among young people.

Crucially, setbacks were more severe across all subjects and grades in disadvantaged social groups, where students have to deal with added trauma, including lack of digital resources, economic dislocation, and even hunger.

Recovering from lost learning will require a coordinated and continued effort.

In the short term, further damages must be stopped; this means fast improvements in distance learning for those students who still cannot fully return to in-person classes. In the long term, the priority must shift to catching up accrued losses, i.e. by offering intensive support, lengthening school days or shortening vacations for students who fell behind.

The future of a whole generation depends on this. The impact of the pandemic on academic outcomes will take years to play out and risks having devastating consequences, since lasting learning shortcomings will make it hard to access higher education or even lead to premature drop-outs, and ultimately ruin the prospect of higher earnings and better life outcomes.

1 In a sample of eight OECD countries plus China.